Reaching for the stars: the UNI alum and astrophysicist behind James Webb Space Telescope launch

Reaching for the stars: the UNI alum and astrophysicist behind James Webb Space Telescope launch

Since the earliest days of civilization, humans have searched for meaning in the stars and wondered if there is life beyond Earth.

Now, we’re moving one step closer to uncovering one of life’s greatest mysteries, thanks in part to the work of UNI Department of Physics alum Christopher Stark.

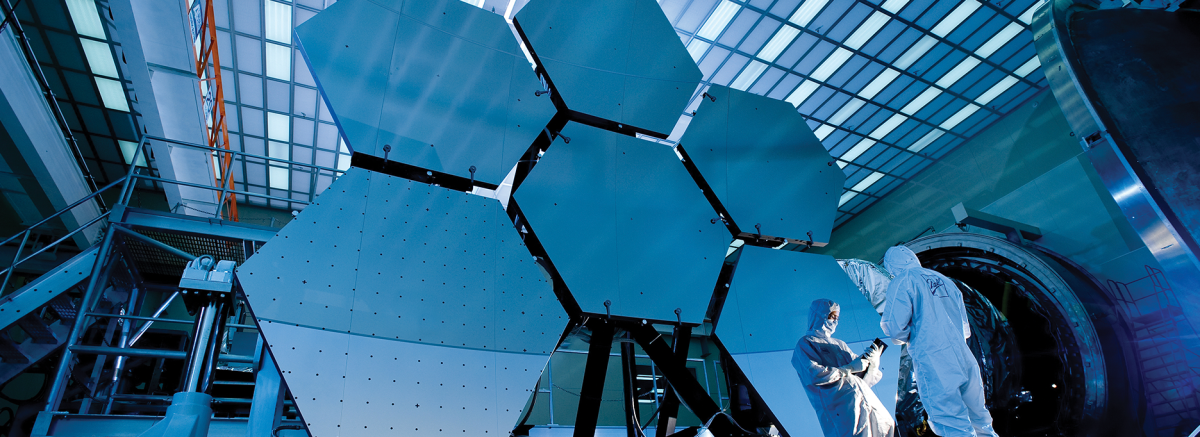

Stark is an astrophysicist in the Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Most recently, he was appointed as the Deputy Integration, Test, and Commissioning Project Scientist for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – which made history in December of 2021 as the most powerful telescope to ever be launched into space.

The telescope will document the earliest stars and observe galaxies farther into our universe’s past than ever before. The impact of this work could change what we know about the universe forever, and of course, it was no easy feat for Stark and everyone else involved.

“Launching was probably the most stressful thing I’ve ever done, but it was also an incredibly exciting and thrilling moment,” Stark said. “It was powerful to see, and you could feel the relief in the room once things started going well. Knowing how many people put decades of their life into this, to have it pay off was really moving.”

To pull something like this off is incredible, Stark says.

“For everything to have gone as well as it did is a testament to everyone who had a hand in this – those who are operating it, those who designed it, and those who built it,” he said. “There’s a tremendous amount of workmanship that went into making this successful.”

Now that JWST has launched, deployed, and had its hexagonal mirrors aligned to work like one large mirror, scientists and engineers are busy calibrating JWST’s scientific instruments for operation. Soon JWST will start its scientific data collection, and top astronomers around the world will compete to make observations using the telescope.

“The JWST is going to unveil parts of the universe that were previously hidden,” Stark said. “We’re able to look 13 billion light years away, seeing the faintest galaxies – effectively the first galaxies ever formed. This is our first opportunity to see those parts of the universe – that’s remarkable.”

What Stark loves most about his work, he says, is being able to play a role in scientific advancement in space.

“I love problem solving, and that’s really what NASA is all about – solving problems that haven’t been solved before,” he said. “I get to collaborate every day with brilliant, inspiring colleagues. I can think of no better reason to get up and go to work in the morning.”

Finding his calling

Tracing back to his early days, some might be surprised to learn that Stark didn’t have much of an interest in outer space growing up – despite having an abundance of opportunity to do so.

“It’s a funny story, really,” he said. “I had every chance growing up to get interested in science and space, and I just didn’t.”

Stark grew up in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, birthplace of famous astronomer James Van Allen, who discovered the Van Allen radiation belts around Earth.

“I went to Van Allen Elementary School, and my parents lived in Van Allen’s former childhood home,” he said. “My dad led the local chamber of commerce and at one point invited a NASA astronaut to give a talk at the town fair. He ended up coming over to our house afterward for dinner and I sat in his lap for a photo and got his autograph.”

While Stark looks back on this with fondness, it wasn’t exactly a transformative experience for him. By the time he got to college, Stark wasn’t really sure of what he wanted to do with his life. He enrolled at UNI to study business – following in his older brother’s footsteps – but it wasn’t where his passion was. Eventually, Stark’s brother encouraged him to take the Physics of Everyday Life course, and that changed everything.

“I was instantly enthralled,” he said. “I was learning to see the world in a way that I never had before, and applying math in ways I’d never thought of. So, I switched my major and never looked back.”

The next four years were some of the best of his life, Stark said.

“I loved physics and I loved UNI,” he said. “They made a scientist out of me. They gave me all the tools I needed, taught me to think critically and objectively about the world around me, and to break down intractable problems into manageable tasks, which is a lot of what I do now,” he said. “I also had a lot of opportunities to publish papers, give talks, freely explore research opportunities, and find what inspired me. I had all of the opportunities you could imagine as an undergrad.”

Dr. Paul Shand, head of the UNI Department of Physics, was a personal mentor to Stark during his time at UNI.

“Dr. Shand was exceptional, and is to this day, by far the best professor I’ve ever met. I don’t think I’m alone in saying that,” Stark said. “I researched with him for a few years, and he helped me — a former business major — navigate a completely unknown career path. Without his guidance, I wouldn’t be where I am today.”

Shand, in return, says he’s honored to have taught such an exemplary physicist, and person, as Stark.

“To have taught and mentored Chris Stark is one of the highlights of my life,” Shand said. “Chris is quite clearly a world-class physicist who is undoubtedly one of the reasons that the James Webb Space Telescope has worked flawlessly thus far. I will always remember that as an undergraduate in his first year of research, Chris found a mathematical error in a paper published in a top physics journal. That’s when I knew that he was special. But the fact that Chris is brilliant is not what makes me overflow with pride; rather, it is because he is an exceptionally decent and kind human being. It was a privilege to spend so much time with him.”

Launching his career

Of all Stark’s experiences at UNI, there is one that stands out above the rest. During one of the department’s many colloquiums, Stark remembers a guest lecturer who gave a talk on exoplanets – planets that orbit stars outside the solar system. “A light bulb went off, and I knew exactly what I wanted to do,” he said.

With encouragement from the UNI physics department, Stark applied to the University of Maryland, which is conveniently located about 10 minutes from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. He went on to earn his Physics Ph.D. from the institution while researching at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center as a Graduate Student Researchers Project Fellow. He then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism and later at NASA Goddard once again.

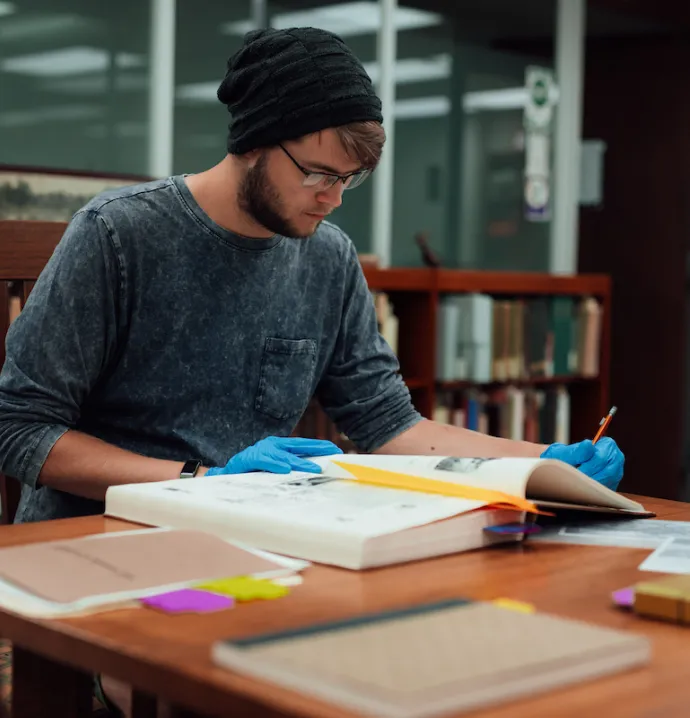

Stark’s research focuses on design and optimization of missions to detect potentially Earth-like planets. In particular, he studies debris disks – the hazy clouds of dust generated by asteroids and comets around other stars. By looking at the properties of this dust and the interaction between exoplanets and disks, he’s able to infer the presence of planets around other stars.

All of his work has culminated in the launch of not only the James Webb Space Telescope, but also an exciting and fulfilling career. Looking toward the future, Stark says he’s eager to see what the JWST will discover in the furthest depths of the universe, but also what will come after JWST. “I’m very excited about what astronomers will discover a few decades from now,” he said. “That’s a long wait, but there’s good reason to be optimistic.”

Recently, the National Academy of Sciences released a 10-year review of the field of astronomy, and delivered a report to NASA with recommendations for future areas of research. Key recommendations include a future mission to image Earth-like planets around other nearby stars – something Stark strives to help see to fruition.

“I feel like all of my research and experiences have led up to this, and I hope to contribute to that mission,” he said. “Does life exist on other worlds? Humans have asked the question for millennia, and now we can finally build the tools we need to go looking for it. That’s the mark I want to leave.”