Ten Days for Trading

Ten Days for Trading

By this clearly stated policy, how is it possible that you selected your elderly 78-year old mom to serve on the Company’s Board of Directors and as a full-time employee providing employee and unitholder services? We further wonder under what theory of corporate governance does one’s mom sit on a Company board. Should you be found derelict in the performance of your executive duties, as we believe is the case, we do not believe your mom is the right person to fire you from your job. We are concerned that you have placed your greed and desire to supplement your family income — through the director’s fees of $27,000 and your mom’s $199,000 base salary — ahead of the interests of unitholders. We insist that your mom resign immediately from the Company’s board of directors.

Daniel Loeb – Letter to Star Gas Inc., 2005

Hedge fund activists go to great lengths pleading their case for why firms that they recently invested in require an overhaul. Nothing is off-limits — not even relatives of corporate managers. After taking a significant ownership stake in the firm, hedge fund activists initiate these public campaigns to rally support among fellow shareholders. The activist’s intent is to invoke substantial change to the management or operations of the firm that ultimately results in a greater share price. These public campaigns are expensive for the activist and gathering shareholder support is critical for the profitability of their investment in the firm. Frequently, activists look to push out existing management and have their hand-picked individuals elected to the firm’s board. Such an outcome requires the voting support of fellow shareholders.

Though public shaming of corporate managers is arguably more entertaining and attention grabbing, the current regulations around activism and stock ownership give activists the opportunity to use other opaque tactics to drum up shareholder support. In particular, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) mandates that any individual who acquires beneficial ownership of more than five percent in a firm, a threshold traditionally met by hedge fund activists, has 10 days to file a Schedule 13D or 13G with the SEC. This 10-day window begins on the day in which the 5% threshold is surpassed. Unless you are Elon Musk, these guidelines are regularly followed, given the litigation threat posed by the targeted firm and the SEC. However, the current regulation provides no clarity on what can occur during the 10 full days, let alone any explanation for why exactly 10 days are so critical.

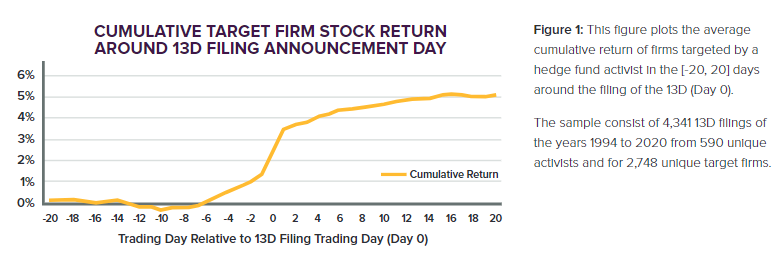

At first glance, it may seem this 10-day window is insignificant. Yet, advanced notice of an upcoming 13D filing by a reputable hedge fund activist can be immensely valuable. In figure one, I plot the cumulative return investors could achieve if they were able to buy the target firm’s stock price in advance of an activist 13D filing for the respective firm. Specifically, I collect 4,341 13D filings over the years 1994 to 2020 from 590 unique activists. I then assemble the collection of stocks of the target firm from each respective 13D filing. As shown in the figure, investors achieve very little return if they were to buy the target firm’s stock price 20 days before (i.e., day -20) the 13D filing announcement and hold this stock until one day before (i.e., day -1). However, if this investor continued to hold the stock through the announcement and for the subsequent 20 days, this investor would achieve a return of roughly 5.2%, on average. This is a sizeable return for a relatively short holding period, making this information valuable to have in advance.

Given the value of advance notice of a 13D, one must ask, are activists selectively disclosing their ensuing campaign plans before they formally file their 13D with the SEC? By activists sharing this Information before it is released publicly, they could use the stock price jump at the announcement as a reward for voting support during the campaign. In recent joint work with Matthew Souther and Choonsik Lee, forthcoming in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, we use Internet Proxy (IP) data of institutional investors to identify “suspicious” access of target firm financial statements immediately before the public announcement of a hedge fund activist’s 13D filings. Although relatively infrequent, the connections we identify between various institutional investors and specific hedge fund activists suggest a pattern of shared information in the days leading up to the activist’s 13D filing. Furthermore, we find that hedge fund activist campaigns associated with suspicious connections perform better and have greater support from shareholders during the campaign. That is, activists of these campaigns are more likely to win their proxy contest, ultimately getting their candidates elected to the board of directors. Such evidence is exactly consistent with activists sharing the ensuing 13D plans with a select group of institutional investors, trading the 13D announcement return for voting support later on in the campaign.

One might give the proverbial “so what” to this finding. After all, the 13D filing guidelines set forth by the SEC makes no mention of whether an investor can share anticipated plans of a 13D in the 10-day filing period. Yet this information is clearly non-public and the announcement returns in Figure 1 suggest the information is indeed material. Additionally, the 10-day window has drawn the ire of senators and SEC regulators. In 2016, Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin proposed The Brokaw Act, a piece of legislation brought about by hedge fund activist Starboard Value’s campaign against the Wausau Paper Company. This campaign was associated with the closing of a Wausau paper mill that happened to be the primary employer in the town of Brokaw, Wisconsin, and whose closure decimated the local economy. The bill proposed changes to 13D requirements, including giving the SEC more authority in determining whether investors collaborated as a group and shortening the days with which an activist has to file their form 13D to less than 10. The Act has thus far remained unpassed and has struggled to gain traction, partially due to the absence of empirical evidence of collaborative efforts between investors.

Our study helps move this bill along as we are the first to present evidence suggesting that hedge fund activists may benefit from the presence of other investors who are informed of their actions. Additionally, the SEC recently proposed revisions to 13D legislation that would regulate informed trading during the pre-13D period more explicitly. The proposal borrows from the rules laid out in the Brokaw Act. These kinds of legislation will likely be passed in some form since many aspects have bipartisan support. A more important question is whether such legislation will modify activist behavior. I have my doubts as regulation rarely has the intended consequence. Only time will tell.