How UNI faculty are helping to reshape anatomy education across the US

How UNI faculty are helping to reshape anatomy education across the US

State-of-the-art health education isn’t just for med school. At the University of Northern Iowa, future doctors, nurses, athletic trainers and other health professionals can look forward to working hands-on in their very first semester.

In what’s known as the syndaver lab, the opportunities are so cutting-edge that UNI faculty are literally writing the book that’s been adopted at other institutions across the United States and potentially around the globe.

A “syndaver” is a synthetic cadaver. They’re lifelike human models – no emotional shock, no formaldehyde – just a clean introduction to human anatomy for biology students on a pre-med track, nursing students building a foundational knowledge of the body, and future physical therapists and athletic trainers learning the intricacies of the musculoskeletal system.

“The flesh feels like real living flesh. If you use real cadavers, the flesh doesn’t feel real,” says Sheree Harper, assistant professor of anatomy and physiology.

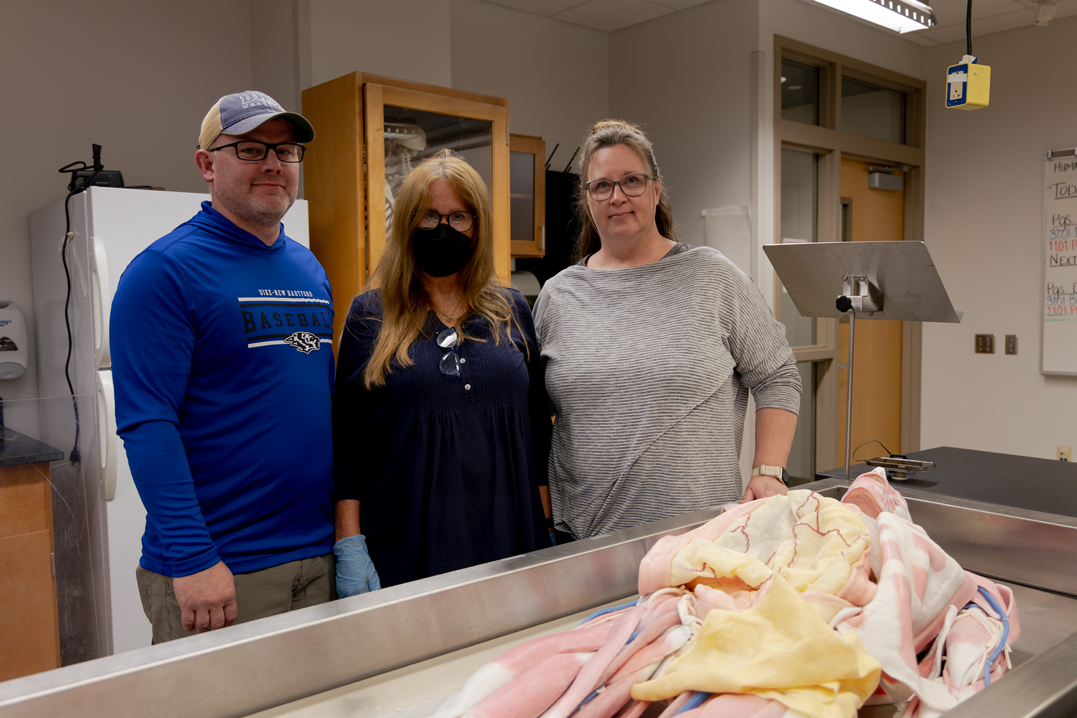

The hands-on experience is accompanied by a custom-designed lab manual, created by Mary McDade, UNI instructor of anatomy and physiology for 35 years, who’s worked closely with the anatomists behind the syndavers. The manual is believed to be the only one of its kind and is now being adopted by other institutions using the syndavers. “It was a lengthy process,” McDade said, “but it’s been well worth it. It gives students something they can follow, step by step, as they study.”

This approach has also produced academic benefits. A statistical analysis conducted by McDade showed significant gains in student test scores after switching to synthetic cadavers: a 12-point improvement on the muscle exam and an eight-point boost on exams involving vessels, nerves and organs.

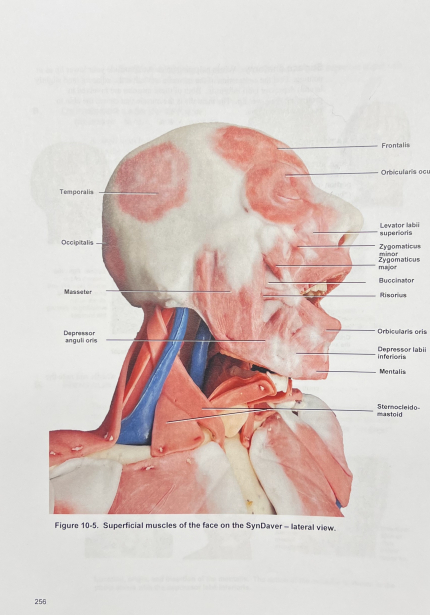

“Mary’s manual does a great job of fanning out the muscles, so that you can see both superficial and deep muscles,” says Harper.

The consistent and replicable design of the models ensures that every student sees the same anatomical structures — unlike real cadavers, where variation can sometimes confuse beginners.

“At a basic introductory level, it’s nice that everybody is looking at the same thing to get the foundation,” says Jim Gronewold, instructor of anatomy and physiology at UNI.

Students use the syndavers throughout much of the semester, often working in small groups that allow for more individualized, hands-on learning. The program at UNI stands out in Iowa for owning four of the models, more than any college or university in the state, as most institutions either have just one or continue to rely on animal dissection. Faculty hope to acquire more in the near future.

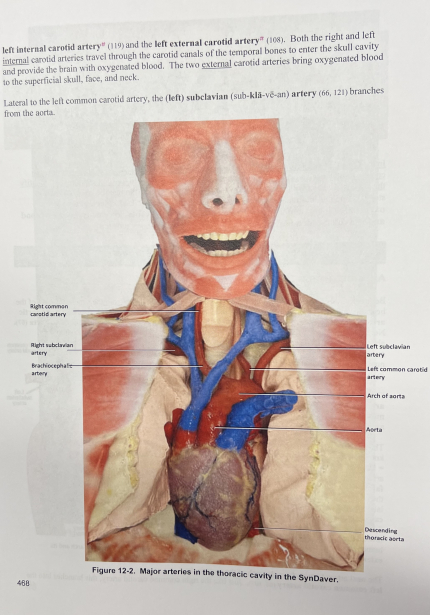

Made from a mix of chemicals that mirror the proportions found in human tissue, syndavers offer students the chance to study muscles, nerves, vessels and organs in realistic detail. For first-year students in particular, the difference is not only practical but emotional.

“To come in and find a real cadaver can be pretty traumatizing,” says McDade. “There are a lot of emotions involved. Sometimes they can’t even focus.” Syndavers provide a more approachable alternative, giving students the chance to engage deeply with the material without the sensory and emotional parts of traditional dissection.

Each synthetic cadaver can be updated annually, with UNI’s lab sending them back to the manufacturer for improvements yearly. New arteries, veins, nerves and organs are added as the company continues to refine its models. “Every time they come back, it seems like they have something new,” says McDade.