Normalizing death, one café conversation at a time

Normalizing death, one café conversation at a time

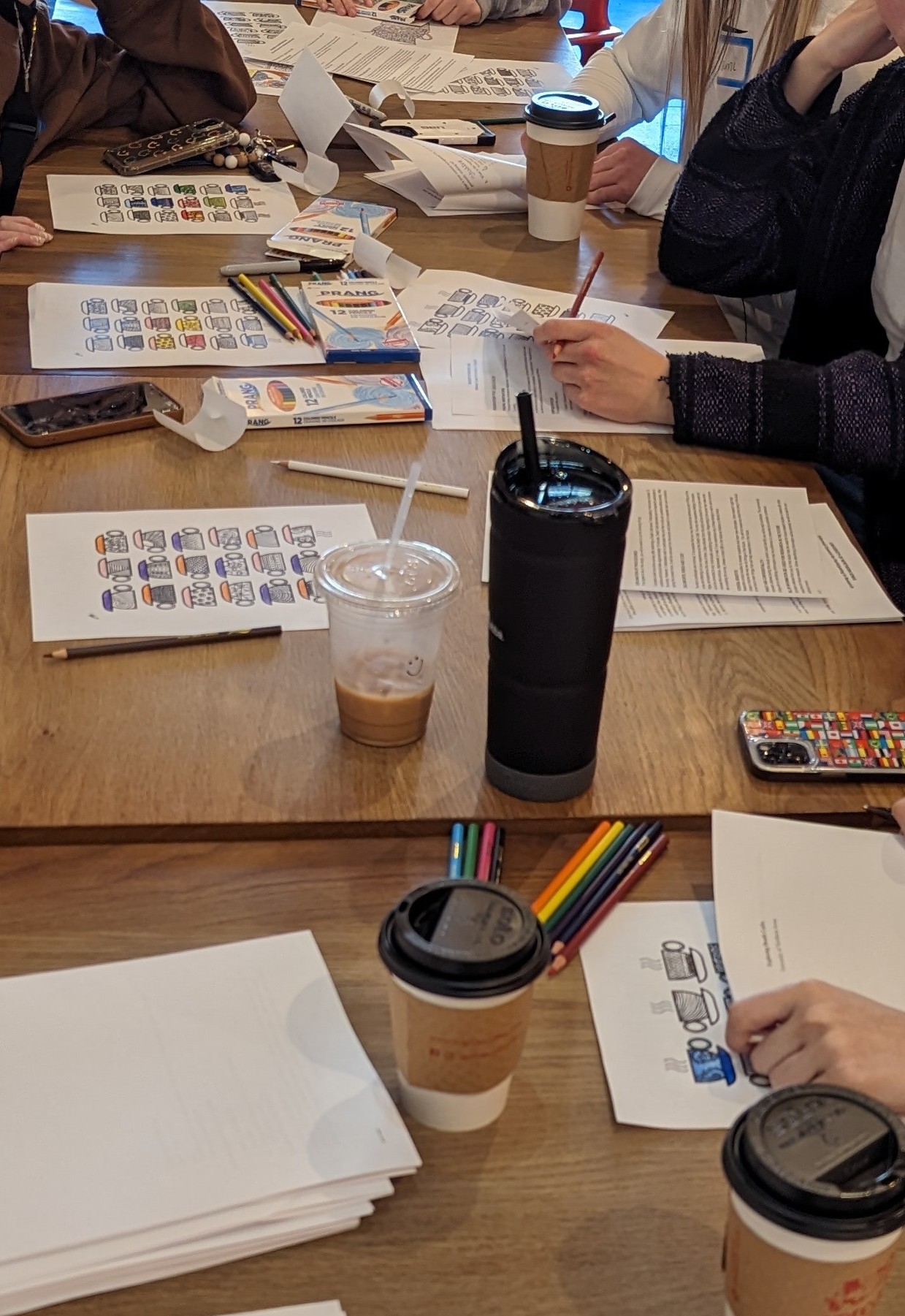

It takes an extraordinary kind of person to handle conversations regarding end of life with a steady head and a compassionate heart. Melinda Heinz, assistant professor in the Department of Family, Aging and Counseling, is just such a person. And she doesn’t limit these conversations to her classroom. In her downtime, she intentionally creates space for these discussions through hosting what’s known as a “death café.”

The concept originated more than a decade ago in Europe and eventually made its way to the U.S. As a facilitator, Heinz organizes and advertises these events, as well as ensures everyone is included in the conversation and no one is pushing their own agenda.

“I feel like there's a need for people to be having more conversations about death because it's something that we're all going to experience: our own mortality and likely the mortality of a family member or friend,” said Heinz. “Since there wasn't anything out there locally, I felt like with my background in teaching end of life issues on campus and my interest in death that maybe I could help start those conversations.”

Heinz’s first death café was held at Sidecar on College Hill in November. Fourteen people showed up, most of whom were college students. There were also a few older adults who were interested in sharing their experiences of attending funerals regularly.

“I think some of them had dealt with a death themselves and were maybe curious or wanting to talk a little bit about that and wanting to hear from other people to see if they had similar experiences,” said Heinz. “Some other students knew that they were going to be encountering death fairly frequently in their major. Knowing this is something they would be interacting with, I think they just wanted to hear from other people about their perceptions of death.”

Heinz saw that the diverse group of people held a wide variety of views on death and dying and coped with it differently.

“We heard from some of the older adults about how they didn't necessarily perceive death as sad,” said Heinz. “They sometimes saw funerals as a social event to connect with other people. So I think that was interesting for the students to hear. I think that many of the older people were much more accepting of death in a way because they are interacting with it so frequently.”

Ultimately, Heinz hopes people walk away from the experiences knowing conversations about death don’t have to be so scary.

“It doesn't have to be morbid or sad or strange,” she said. “We should be having these conversations so that death can be sort of normalized. All of us are going to face death at some point, but we treat it as a hush-hush or taboo subject. It really shouldn't be that way. So I hope people will start to feel more comfortable having those conversations.”

Although this is Heinz’s first academic year teaching at UNI, her journey to gerontology began at UNI as a student. When Heinz first came to study at UNI, she was majoring in communications. At the time, the gerontology major was new, and she learned about it through The Northern Iowan student paper. She was interested enough to meet with a staff member and promptly started taking gerontology courses.

While in graduate school at Iowa State University, Heinz taught a class on perspectives on death and dying. She fell in love with the class and taught it throughout her graduate career.

“I feel a real passion for talking about these issues because it feels like in many cases, people have not had these conversations before and are sometimes surprised about what they uncover about themselves or even family members’ desires for things related to death,” Heinz explained.

Heinz briefly worked in long-term care before moving to academia. At UNI, she has taught Families and End of Life Issues, Families and Aging, and Family Relationships. She believes normalizing death through these classes and her work with death cafés is especially helpful for students who will frequently encounter death in their careers.

“For our students in gerontology and family services, especially, they're going to encounter that a lot, whether they think that they will or not, and being prepared to deal with it is really important,” she said. “So, being comfortable having hard conversations and being comfortable with comforting is crucial.”

Although some might have extreme difficulty teaching about death, Heinz has a different perspective.

“I think about it more in terms of trying to make the most of life that we do get to have,” she said. “Because I teach about it on a daily basis, I’m reminded that we only have so much time and so we should be spending that time wisely. We should be engaged in things that give us purpose and meaning and make us feel fulfilled. I love what I’m teaching because it's a daily reminder to do what you love, find your passion and not waste time.”

Heinz will be hosting at least two more death cafés during the spring semester:

- Jan. 31 from 12:30 to 1:30 p.m. at the Dementia Simulation House.

- Feb. 28 from 7 to 8 p.m. at the Cedar Falls Public Library.