Remaking history

Remaking history

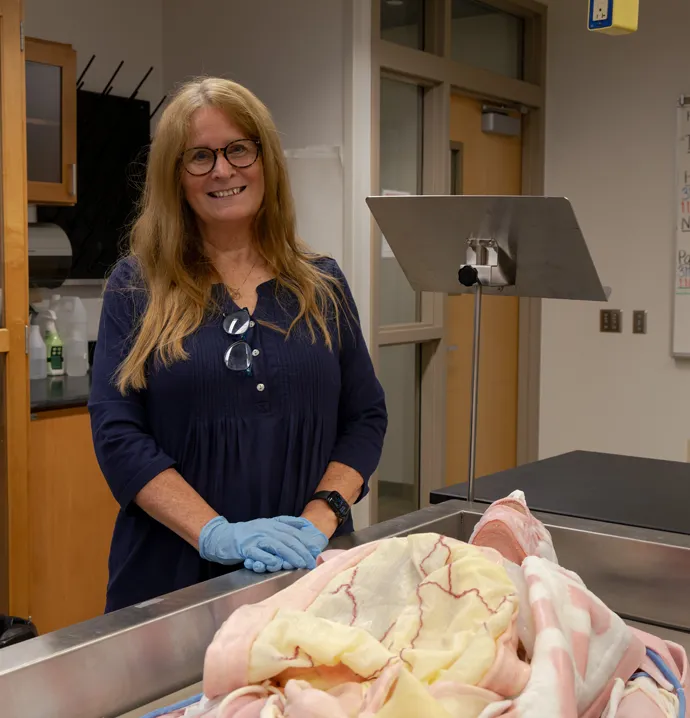

It’s not hard to see why Alison Altstatt’s friends call her “the Indiana Jones of medieval manuscripts.”

Though Altstatt may not be fighting Hollywood villains while sporting a fedora, her adventures have taken her around the globe – discovering long lost artifacts of the past.

Her mission: to recover and reassemble the pages of a precious 13th-century musical manuscript – all while balancing a full teaching schedule at the UNI School of Music.

The first piece of the puzzle

Growing up, Altstatt always had an appreciation for the intersection of history and music. She wanted to know more about the people who created the music she sang in church, or the meaning behind some of the Catholic musical traditions she’d been raised with.

Eventually, that curiosity led Altstatt to get a Ph.D. in Musicology, with a second field in Historical Performance Practice. Her research focuses on the music and rituals of Benedictine convents, along with medieval manuscripts and their twentieth-century reception – something she integrates into the music history classes she teaches at UNI.

Through her teaching and research, she’s crafted a vast network of connections in the music history, art history and liturgy fields, and carved out a name for herself as an expert in her area.

Colleagues often call on her for help identifying or examining historical musical pieces. So when a friend at University of Iowa Special Collections asked Altstatt to look at several old manuscript pages, it didn’t seem like a big deal at the time.

Until it was.

While inspecting the pages from the U of I Special Collections, one in particular stood out to Altstatt.

“I was looking at this one leaf, which was a fragment of a dramatic play, where the only known examples are from England, but this was in Latin and written much earlier than expected,” she said. “It got me excited. Reflecting on it later that night, I realized I had seen a page like that before.”

During her time at Indiana University, Altstatt researched pages from an old manuscript called “The Wilton Processional.” It was a collection containing poetry, drama, music and liturgy from the famed Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire, England.

The original manuscript had been missing since 1860, after a book dealer disassembled it and sold it piece by piece to buyers around the globe. Altstatt realized she wasn’t studying just any manuscript — she was studying a page of the infamous “Wilton Processional.”

Reframing the picture

Over the next several years, it became Altstatt’s personal mission to recover and reassemble the missing pages of the manuscript.

On several occasions, she flew to England to perform field research – visiting the site of the abbey, where only fragments remain now, and walking the hills where the nuns once walked in processionals. She also continued her research at home, pouring over information she found online, and following each trail of clues to the next page.

So far, Altstatt has managed to track down around 50 pages of the manuscript – but there’s still much work to be done, with more than 100 pages still missing. With all of the effort that Altstatt has put into this project, some may ask ‘why?’ What’s so special about this manuscript?

Aside from being one of the oldest surviving processionals, it also gives a rare glimpse into the lives, history and traditions of women in medieval England. “During this time in history, women were very rarely represented,” Altstatt said. “If they were represented at all, it was by a male historian or witness who wrote about them through his own account. Now, through this manuscript, we have an inside look at what life was like for women, and the rituals, customs and traditions that they created and performed.”

This idea of the people behind music – particularly underrepresented populations, is a driving force not only in her quest to reassemble the “Wilton Manuscript,” but also in Altstatt’s teaching.

“The history of a piece of music, and the context of it, is just one more layer to really understand a musical composition,” Altstatt said. “What is its origin? What drove its composition? What is the context in which it was performed? My hope is that by studying music history, my students will be better prepared to understand the meaning in all of their musical pieces. Understanding the history makes the music mean so much more, and you can really appreciate what it meant to the people who created it.”

In specific, Altstatt tries to share different musical narratives with her students. “Often, women’s musical lives are left out of the narrative, and it’s important for me to represent diversity of that kind in my classes,” she said. “We studied a medieval music composer Hildegard of Bingen in one of my music history classes. She’s a fascinating figure, and you could see part of the room light up. The women in the room are excited to see themselves represented, when so often, you only hear about male composers.”

Part of the fun of music history, Altstatt says, is discovery. While she pursues discovery in the form of a medieval manuscript, she encourages her students to pursue discovery in the classroom.

“I try to find different modes of teaching that allows students to discover things themselves,” she said. “By performing read-alouds and movement/dance, we figure out ways to make the study of history experiential. It’s always fulfilling for me to watch students mature over the course of the class. By the end, they’re doing their own research and making their own discoveries.”

Sharing the story

All of Altstatt’s work recovering the “Wilton Processional” will be compiled in her new book “Wilton Abbey in Procession,” which she hopes to publish by 2022. She’s already secured a deal to have the work published in Exeter Studies in Medieval Europe, published by Liverpool University Press.

Her hope is that by sharing this piece of musical history with the world, it will help shine a new light on a different aspect of musical history that isn’t as visible. “Ultimately, it would be a dream come true to compile every page of the original manuscript into a digital reconstruction of the book that users can leaf through, and to share that publicly,” she said. “There’s still a lot of work to be done, but the work is very collaborative, with more and more people turning up pages around the globe, so there’s hope.”

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2020 edition of Communique, the College of Humanities, Arts and Science’s alumni magazine.