How one UNI professor is helping guide pandemic ethics

How one UNI professor is helping guide pandemic ethics

Normally, Francis Degnin’s bioethics class would be spending the spring semester discussing hypothetical questions of ethics in the medical field.

Instead, they’ve now found themselves discussing real life issues facing doctors and nurses around the globe, as the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps through nations and overwhelms health care systems.

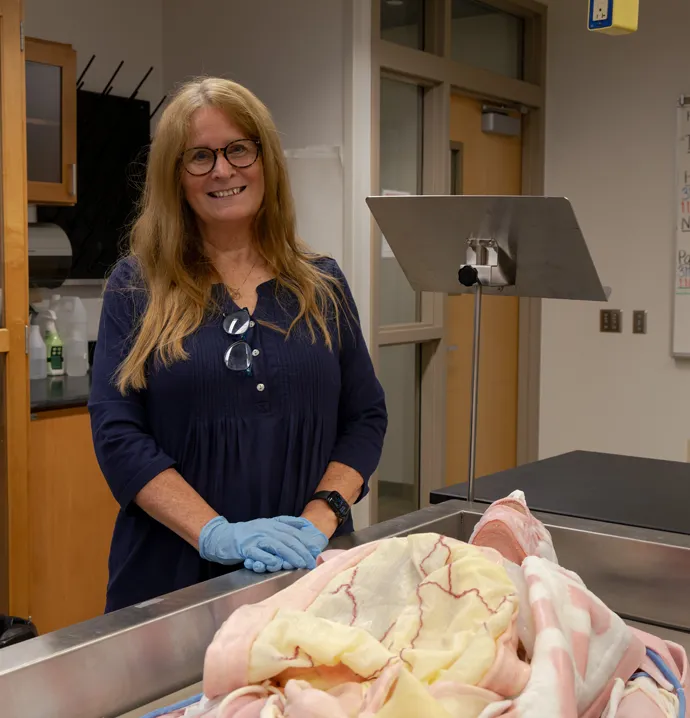

Degnin, an associate professor in the UNI Department of Philosophy and World Religions, is uniquely positioned to help in this scenario.

As an ethicist specializing in clinical (medical) ethics, which is a branch of applied ethics that studies the philosophical, social and legal questions and issues arising in medicine, Degnin has been called upon for guidance by local hospitals and health care organizations.

Here, he discusses the important role that ethics plays when facing a pandemic, and how he’s using his expertise to help the local community:

You teach philosophy at UNI, and specialize in medical ethics. Can you tell readers a little bit about what that means?

Sure. I specialize in Clinical (Medical) Ethics, and I was trained via a two year hospital fellowship to negotiate actual cases in hospitals and other clinical environments. Aside from teaching, I serve on the Ethics Committees for both local hospital systems. I do case consultation, policy review, and education for Ethics Committees, nurses, physicians, chaplains, and social workers. I also serve as a resource for the Northeast Iowa Family Practice Residents, serve on the Iowa Veteran's Home Ethics Committee in Marshalltown, and on the Legislative Advisory Committee for Inherited and Congenital Disorders. When it comes to ethics, much of my work focuses on educating these various groups.

How do ethics come into play during a pandemic, and why is it important to have these types of discussions right now?

The issue came up with H1N1 about 10 years ago. There was a concern back then that it might become a pandemic. As the Ethicist for a local hospital system, I conducted a series of input sessions with physicians, and looked at the Iowa Pandemic Ethics Policies in order to develop a policy, or at least a guideline, for how to make ethical triage decisions if the health care system was overwhelmed with patients. More recently, I've been updating and virtually presenting to local hospitals’ Ethics Committees and Pandemic Response Teams based on COVID-19. Just within the last week, I was asked by a hospital to review a policy it was considering adopting on pandemic triage.

To be more specific, what types of ethical questions are hospitals and medical professionals currently dealing with?

There are a lot of questions right now, such as: How does ethical decision making change in a pandemic? Some places are considering DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) orders on all COVID-19 patients, so what are the ethical arguments for and against that? How do we decide, if we don't have enough ventilators and beds, who lives and who dies in a way which isn't arbitrary and which doesn't account for privilege, for example, those with wealth and power? These are things I’ve discussed with local hospitals, and they’re also some issues I’ll be discussing in my bioethics class in the coming weeks.

What’s one important thing for people to know during a pandemic such as this?

It’s important for people to receive the correct information. There are a few significant items of misinformation that were provided early in this pandemic. The first was really from President Trump, that they could stop COVID-19 at the airports by taking temperatures. Many viruses are contagious a day or two prior to symptoms, and even if this wasn't one, there's still an incubation period before a fever, if any, will show up. So anyone with a basic medical knowledge knew that that claim was false. It may have been perpetuated for good reason (to avoid panic), but it was clearly false. This relates to the second as well: the guidance not to wear masks. Again, most likely given for a good reason. Since there was a shortage of masks, the CDC wanted to preserve them for the medical professionals, who are at the highest risk for the disease, but it was still misleading at best. What they actually said was that masks would be unlikely to keep you from getting sick. And that's true, unless it's an N-95 mask. But if we all started wearing a regular surgical mask in public, anyone who was contagious and might not know it (due to being early in the illness or having a mild case), it would have helped to slow the progression of the virus. So, while wearing most masks doesn't help keep ME from getting sick, it helps others from getting sick from me. (China estimates that universal masks slowed the virus by about 50%.) It’s very important that people receive clear and correct information.

Clinical ethicists like yourself work largely behind the scenes, but still provide critical assistance to hospitals and healthcare organizations. What drew you to this type of work in the first place?

I tell my students that my job isn't always pleasant, but it's rarely dull. I'm not needed for the routine stuff; I get called when there is a particularly difficult or dynamic issue. The big thing is that care for real people in real life grounds my thinking, while the critical and philosophical tools I develop in my research enhance what I offer in the clinic. Not only do I get to help people, but that service comes to inform my research and teaching. Clinical Ethics is sometimes called a "secular priesthood." I was raised Catholic with a strong sense of service; I even went to seminary. I didn't stay, in part, because I didn't want to have to fit into a particular theological hierarchy. I'm much more attracted to the service and social justice side of things. Philosophy gave me more freedom of thought, and when I discovered clinical ethics, it was a natural fit.