Ahead of the game

Ahead of the game

Gone are the days where video games are seen as a simple pastime. Instead, they are a force to be reckoned with – holding an integral place in modern day society, entertainment and culture.

In recent years, the video game industry has experienced explosive growth – thanks in part to the pandemic, which saw millions of new players logging on during lockdown.

Last year, the video game industry brought in more than $200 billion, and by 2030, that number is expected to grow to a staggering $500 billion.

Video games are now one of the fastest growing economic sectors – five times bigger than the movie industry, according to the FTC.

In 2023, the Grammy Awards unveiled the first ever dedicated award category for video game soundtracks. On streaming apps like Spotify, a single album from a game soundtrack (Undertale) garnered close to 1 billion streams, with other game soundtracks not far behind.

Music is an integral part of the gaming experience – helping to immerse the player in the game, build mood and signify emotion, and serve as a guide throughout the gaming journey.

As more players continue to flock to video games, it only makes sense that fields like Ludomusicology (the study of video game music) will continue to grow alongside it, and the UNI School of Music is helping students stay ahead of the game.

This spring, a group of students had the opportunity to take part in a brand new independent study seminar centered around the study of video game music (Ludomusicology).

Led by Alison Altstatt, Associate Professor of Musicology and Music History, the class was sparked by student interest.

“[The idea for the seminar] started with a student request,” She said. “This is not my area of research and I know very little about video games and video game music, but I’ve been challenged in recent years by students who want to learn about it and research about it. When possible, I want them to learn about things that are of interest to them, and I became aware this was an area of passion for a number of students, so we decided to try it out.”

The students helped design the class and determine some of the topics they wanted to discuss, and Altstatt used her expertise in musicology to give them the analytical techniques and interpretive perspectives to learn, write and research video game music in a musicological way.

“I think what makes this [Ludomusicology seminar] special for UNI is we are so student-centered,” she said. “We pride ourselves on listening to students and responding to what they are curious about. And during this seminar, the students really stepped up, and I was learning from them as much as they learned from me. I think it was good for them to confirm this is a respected area of scholarly interest, and they also gained some musicological chops.”

Jacob Chaplin, a junior music composition and bass trombone performance, says the class was eye-opening for him.

“Growing up, I spent a lot of time playing video games, and I still do,” he said. “One of the reasons I got into music was by playing video games and really liking what I heard in the soundtrack. For me, it’s really great to see the acceptance of [video game music] becoming more prevalent in academia. Institutions are willing to give this genre a chance because the person who wrote that music obviously had to have a lot of skill and knowledge, and it doesn’t make the music any less respectable because it has Mario in front of it rather than a guy waving a stick.”

Chaplin said he enjoyed the chance to not only hear about his peers’ game experiences, and to learn from professionals in the field, but to dive deeper into what video game music means.

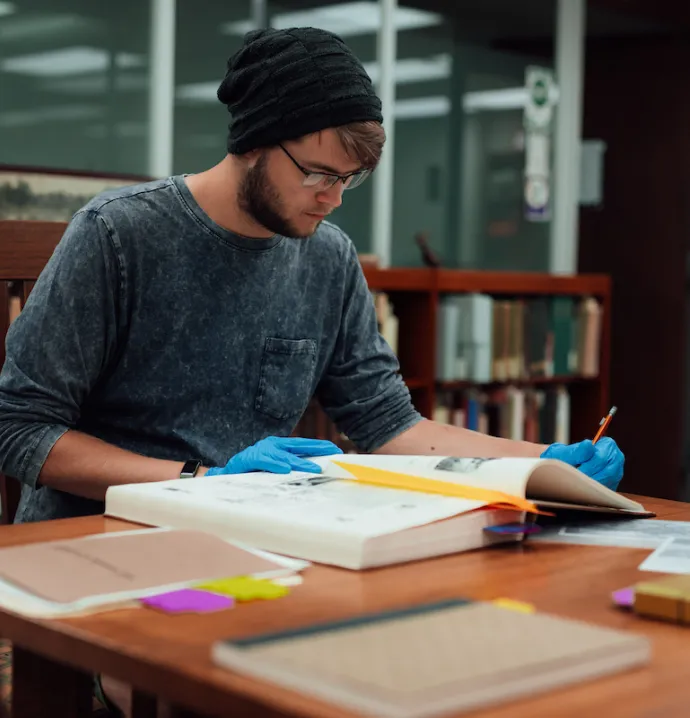

During the class, students had the chance to virtually attend the tenth annual North American Conference on Video Game Music where they learned from leading scholars in the field. They also worked throughout the semester on independent research projects to analyze music from a video game of their choice, which they presented in front of the campus community during the annual INSPIRE conference.

The class culminated in the preparation of a museum exhibit designed in collaboration with Jess Cruz, Exhibit Coordinator and Outreach Educator for the UNI Museum at Rod Library.

Cruz worked closely with the students throughout the semester to craft the exhibit, which explores the field of Ludomusicology, gives a deeper look into the class and showcases students' individual research projects in greater detail. The exhibit is on display in the Russell Hall lobby through the fall of 2023, and is open to the public.

For the students involved, having the chance to showcase their work to the public – both at the INSPIRE Conference and through the exhibit in Russell Hall – has been a gratifying experience.

David Phetmanysay, who graduated in May with a degree in Viola performance, says the class was one the highlights of his time at UNI.

“I loved the class so much,” he said. “I have been an avid gamer my whole life, and at the same time, had a longtime interest in music. I really like how everyone in the class was very invested and wanted to be there because they have such a passion for video games and video game music.”

Phetmanysay and Chaplin agreed that they’re glad the field of video game music is becoming more widely accepted as an area of study.

“Just like film music, video game music is building in its credibility as a genre worth studying and worth practicing,” Chaplin said. “Not a single professor at UNI will tell you John Williams isn’t a genius, even if people are swinging laser swords or fighting dinosaurs in front of that music. I think video games are just another evolution of that. If you're a musician, learning new kinds of music is kind of your job. If you intentionally avoid it, you’re limiting yourself. [Video game music is] very good music on its own. Like Skyrim for example – if you played those tracks in a full concert hall in front of your grandparents, they probably wouldn’t even know it was from a video game.”

Both Chaplin and Phetmanysay said that they would like to continue their involvement in Ludomusicology.

Phetmanysay has already written some Minecraft-inspired music, which is currently streaming on Soundcloud, but he says he’d like to someday make a career of writing music for video games.

“To me, writing music for video games is much more interesting than writing classical music,” he said. “In video games, you can do anything you want, and get really creative. Plus, it’s just a lot of fun – the possibilities are limitless when you aren’t confined to certain boundaries. I think the field is going to continue to grow and become more relevant, and that’s very exciting to me.”

Apart from being a growing career field for music students, Altstatt says the field of Ludomusicology is important because of the vast impact video game music has on people across the globe.

“People, especially young people, all over the world listen to video game music for hours every day, and unofficially, it has a big impact,” Altstatt said. “I suspect that the field of Ludomusicology will only continue to grow, just like the study of pop music or film music developed and grew. As long as video games are with us, expanding to different platforms and apps, the interest in video game music will be there, too, because people are experiencing it on a daily basis.”

On a more personal level, the Ludomusicology course at UNI was a great experience for Altstatt as a faculty member.

“For me as a teacher, teaching gets stale if I’m not always learning,” she said. “Sometimes I learn from experiences that I wouldn't necessarily have sought out myself. I’m constantly learning from our students. They’re so ambitious, disciplined, and curious. There’s only so much I can get to in the music history core curriculum, so what's important for me is that they develop tools they can add to their toolbox as performers, teachers, scholars and that they develop confidence in themselves and their capacity to describe, analyze and explain the importance of different types of music. If I want to encourage them to be open minded and curious, I need to model that myself, and for me, this opportunity really enriched my experience. Plus, this is an area of music that’s really meaningful for a lot of [our students], so it’s great for them to be able to work on music that they’re familiar with and invested in, that you might not normally have a chance to talk about in a classical music school.”

Altstatt says she has more students interested in the Ludomusicology seminar, and she’s already planning another course next spring.