Cicadas in the classroom: Learning math through nature-inspired kids game

Cicadas in the classroom: Learning math through nature-inspired kids game

The cicadas are coming. A large portion of the United States, including northeast Iowa, is experiencing the emergence of not one but two broods of cicadas after years underground.

The natural phenomenon inspired a unique math game for children. Chepina Rumsey, an associate professor of mathematics education at UNI, created the Cicada Game more than a decade ago. Alongside a thematic unit teaching math, science and language arts created with another faculty member, the game has been published in Science and Children, a practitioner journal of the National Science Teachers Association. It’s relevant today more than ever.

“Having this publication coincide with such an exciting natural event like this dual emergence really adds to the excitement for me because I know a lot of people are thinking about cicadas right now,” said Dana Atwood-Blaine, the Jacobson Elementary STEM Fellow and an associate professor of elementary education who created the thematic unit.

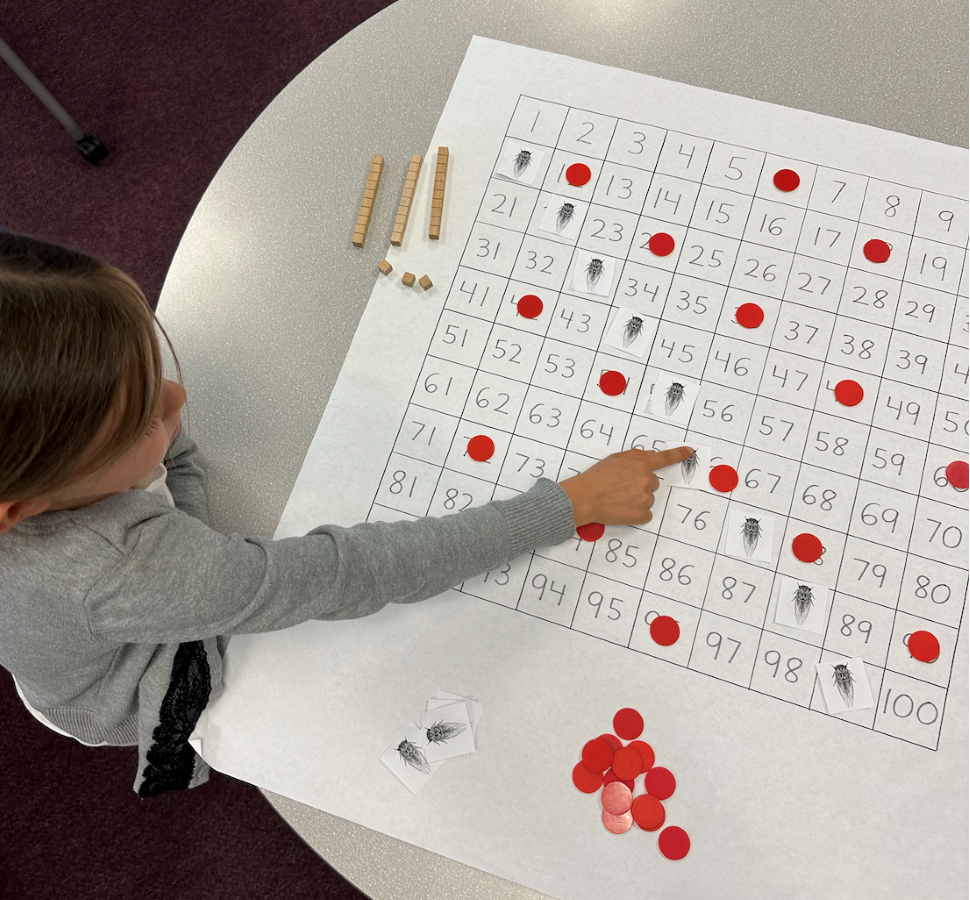

To play the Cicada Game, there must be two opposing players or two opposing teams, one taking on the role of the cicada and the other taking on the role of the predator. The cicada player or team must choose a number between 10 and 20 to represent years spent underground. The predator selects a number between 1 and 10 for their years underground. The players then place markers on a 100s chart to show what years they will be emerging. If the predator’s and the cicada’s years overlap fewer than four times, the cicada wins. If there are four or more overlaps, the predator wins.

This game teaches players important mathematical concepts such as skip counting, multiples and multiplication, prime and composite numbers, factors and the difference between factors and multiples.

“If the cicada picks a prime number, then it'll win the game,” Rumsey explained. “Or if the predator’s number is a factor of the cicada’s number, then the predator will win. Lots of conjectures come out of that.”

Rumsey created the game when she was working with students in an afterschool program in Kansas. At the time, Rumsey, a New Hampshire native, was experiencing the excitement of cicadas for the first time. She loved seeing the children’s enthusiasm over the insect and thought the game would be a great way to draw on that.

“I really like finding games that are interesting and that hit on really important math concepts,” she said. “This one I love because it connects to science and math in such a deep way.”

Rumsey has experience working as a classroom teacher and consulting with a curriculum company to create math games just like the Cicada Game.

A few years ago, Rumsey was collaborating with Atwood-Blaine for a conference presentation. She introduced the Cicada Game to Atwood-Blaine, who then incorporated numerous science concepts to be taught alongside the game. For example, the game is an opportunity for students to learn about how all organisms have similar life cycles and how some animals form groups to help themselves survive.

“I'm always trying to teach my pre-service elementary teacher students the more you can integrate your subject areas, the more your students will be able to connect with them and make meaning from your lessons,” said Atwood-Blaine. “The world is not segregated into math moments and science moments. The world is integrated, and everything we encounter in the world is integrated.”

The unit Atwood-Blaine and Rumsey created even includes some language arts concepts. There is a portion of the unit with poetry that instructs two different people or two sides of a classroom to read different sections of the poem. The two people or groups end up sometimes speaking in unison where sections of the poem overlap, and, when the whole class is reading, it sounds like cicadas.

“I loved teaching elementary school and teaching all subjects and integrating it because that's how the world is,” said Rumsey. “I love that the world is connected like the subjects are connected. Students do feel more engaged, when it's something that they can play and then explore and connect to the real world.”

Since that first conference, Rumsey and Atwood-Blaine have presented on the game numerous times. It was last year that Atwood-Blaine saw the call from Science and Children for content connecting science and mathematics for an issue dedicated to the subject. She knew she and Rumsey had something special to submit.

Interestingly enough, when she found out the submission had been accepted, Rumsey was with her family in a Chicago area admiring cicadas.

“We ended up going to an arboretum, and the cicadas were everywhere,” said Rumsey. “I just wanted to tell everybody there about the article.”

The game is recommended for K-5 students, and the thematic unit can be utilized for students as young as first grade.

“It’s for young children and all the way through even adults because we did this with our pre-service teachers, and they're learning from it, too,” said Atwood-Blaine. “So this is a very versatile and applicable game for everybody.”